In June 2020, the Quaker Oats Company announced that it would be re-branding its Aunt Jemima line of products — syrup, pancake mix, and other breakfast foods — because the brand's origins were based on racial stereotypes. Kristin Kroepfl, vice president and chief marketing officer of Quaker Foods North America, told NBC News:

"We recognize Aunt Jemima's origins are based on a racial stereotype. While work has been done over the years to update the brand in a manner intended to be appropriate and respectful, we realize those changes are not enough."

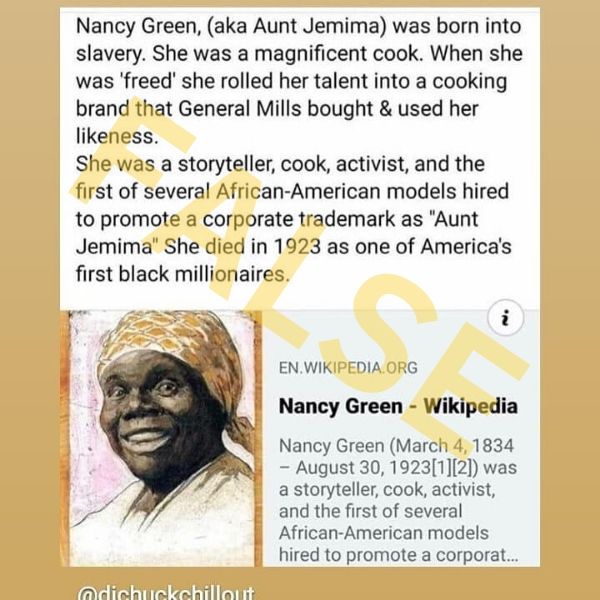

This decision caused some online outrage as social media users accused Quaker Oats of erasing its history and diminishing the accomplishments of Nancy Green, the woman who portrayed Aunt Jemima in promotional materials in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Many of these posts claimed that Green was one of the first African American millionaires because of the amount of money she earned playing Aunt Jemima:

But Green did not die a millionaire. In fact, she could not live off the earnings she made from her portrayal of Aunt Jemima, and continued to work as a housekeeper until a few years before her death in 1923.

But Green did not die a millionaire. In fact, she could not live off the earnings she made from her portrayal of Aunt Jemima, and continued to work as a housekeeper until a few years before her death in 1923.

The Origins of Aunt Jemima

The origins of Aunt Jemima can be traced back to 1889 when Chris Rutt and Charles Underwood created a self-rising pancake mix. The product originally carried the name "self-rising pancake flour," but Rutt was inspired to change the name of the mix after he attended a minstrel show and saw men dressed in blackface perform a song entitled "Old Aunt Jemima."

The Encyclopedia of African American Popular Culture writes:

In the fall of 1889, Rutt was inspired to rename the mix after attending a minstrel show, during which a popular song titled "Old Aunt Jemima" was performed by men in blackface, one of whom was dressed as a slave mammy of the plantation South.

While Rutt and Underwood developed this self-rising mix and contributed the "Aunt Jemima" name, they were unable to turn their product into a commercial success. The duo sold their milling company to R.T. Davis, who, with Green's help, would go on to create the persona of Aunt Jemima and turn the brand into a national product.

Green's World Fair Debut

Davis hired Green, who was born a slave in Kentucky in 1834, to portray Aunt Jemima at the World's Fair in Chicago in 1893. Green, as Aunt Jemima, served pancakes to the crowd and told romanticized "stories" of her time on the plantation. While these stories were presented as if they were the genuine memories of Aunt Jemima, Green was, of course, just playing a fictional character.

In "Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory," author Kimberly Wallace-Sanders writes:

At one point the most reliable means of consolidating the country involved inducing a kind of national amnesia about the history of slavery. Aunt Jemima was created to celebrate state-of-the-art technology through a pancake mix; she did not celebrate the promise of post-Emancipation progress for African Americans. Aunt Jemima's "freedom" was negated, or revoked, in this role because of the character's persona as a plantation slave, not a free black woman employed as a domestic. An African American woman, pretending to be a slave, was pivotal to the trademark's commercial achievement in 1893. Its success revolved around the fantasy of returning a black woman to a sanitized version of slavery. The Aunt Jemima character involved a regression of race relations, and her character helped usher in a prominent resurgence of the "happy slave" mythology of the antebellum South.

[...]

Nancy Green, a former slave from Kentucky, played the first Aunt Jemima. Green was a middle-aged woman living on the South Side of Chicago, working as a cook and housekeeper for a prominent judge. After a series of auditions, she was hired to cook and serve the new pancake recipe at the World's Fair. Part of her act was to tell stories from her own early slave life along with plantation tales written for her by a white southern sales representative. This combination of historic and mythic plantation was designed to perpetuate the "historical amnesia necessary for confidence in the American future." That this amnesia occurred at the expense of African American progress was clearly not an issue for the Pearl Milling Company, the inventor of Aunt Jemima.

A pamphlet detailing the "life" of Aunt Jemima, which portrayed her as a "happy" slave with a "secret recipe" working at a plantation owned by Colonel Higbee of Louisiana, was also created for the 1893 World's Fair, and laid the foundation for future advertisements to build on the Aunt Jemima myth.

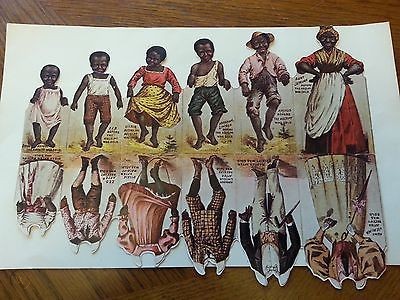

One artifact from the early days of Aunt Jemima's fictional history was a set of paper dolls that supposedly showed Aunt Jemima and her family before and after they sold her secret pancake recipe. The "before" set included six paper dolls without shoes and dressed in shabby clothing, while the "after" set included a set of "fancy" clothes.

But these dolls, like most of the fictional lore surrounding Aunt Jemima, did not accurately reflect reality.

Was Green a Millionaire?

We have been unable to find any specific details about how much Green was paid for her portrayal of Aunt Jemima. The evidence, however, suggests that Green did not become rich from her work and was likely paid a paltry sum.

In "Clinging to Mammy: The Faithful Slave in Twentieth-Century America," Micki McElya writes that in 1900, Green listed her occupation as a "cook." While this may have referred to her job demonstrating pancake mix as Aunt Jemima, in 1910, she was working as a "housekeeper."

In that year (1900) she listed her occupation as "cook," which could have referred to her job demonstrating Aunt Jemima pancake mix or else indicated that her primary employment remained in domestic service. The latter was the case in 1910, when she reported her job as "housekeeper" in a private residence. Performing as the trademarked mammy was not her primary job by that time, if it ever had been.

We reached out to McElya for more information about what monetary payments Green received for her portrayal of Aunt Jemima. McElya couldn't point to a specific dollar amount, but she did say that she "found no evidence that Nancy Green died a millionaire in 1923," and that "the available evidence suggests otherwise."

M.M. Manring, the author of "Slave in A Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima," also told us that "all of the available evidence ... would suggest that [Nancy Green] was almost certainly not conspicuously wealthy." Manring also addressed the notion that Green was given a "lifetime contract" to portray Aunt Jemima. This "lifetime contract," according to Manring, was part of the lore created for the character of "Aunt Jemima" - but there's no evidence that it actually applied to Green.

Manring said:

I've been through the J. Walter Thompson archives at Duke, where so much of the papers related to the Aunt Jemima campaign are stored, and never found any reference to her pay. None of her obituaries mention anything regarding her wealth. If she had a $1 million fortune in, say, 1920, adjusted for inflation, that's the equivalent of about $13 million today, by my calculations. It would be surprising to me if all contemporaneous accounts of her failed to make any mention of her vast wealth.

[...]

All of the available evidence, such as it is, would suggest that she was almost certainly not conspicuously wealthy. She was comfortable enough to give to her church and do missionary work, but so were plenty of other people of ordinary means. As for the "lifetime contract," that was a big part of the promotion of Aunt Jemima. You see the same language in the ads – that a milling company in Chicago brought Aunt Jemima north and gave her a lifetime contract, and even paid her in gold. I have never found nor to expect to find proof of a contract, and again, I can't prove a negative. But I do think you have to put that claim in context with a long-running ad campaign that mixed myth and reality, and people real and imagined.

Obituaries for Green published in The Chicago Tribune and Daily Herald also made no mention of her being one of the first African American women to become a millionaire:

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53701027/

While no evidence exists to suggest that Green died a millionaire, she did make enough money (as both a housekeeper and for her promotional work as Aunt Jemina) to support the missionary work of the Olivet Baptist Church in Chicago.

It should also be noted that Green's descendants (as well as the descendants of another Black woman who portrayed Aunt Jemima) filed a lawsuit against Quaker Oats, arguing that the company exploited Green, and that her family was owed billions in royalties, USA Today reported. The lawsuit was later dismissed after a judge ruled that the plaintiffs did not provide proof that they were related to the women who portrayed Aunt Jemima:

Now, a lawsuit claims that Green's heirs as well as the descendants of other black women who appeared as Aunt Jemima deserve $2 billion and a share of future revenue from sales of the popular brand.

The federal suit, filed in Chicago in August by two great-grandsons of Anna Short Harrington, says that she and Green were key in formulating the recipe for the nation's first self-rising pancake mix, and that Green came up with the idea of adding powdered milk for extra flavor.

"Aunt Jemima has become known as one of the most exploited and abused women in American history," said D.W. Hunter, one of Harrington's great-grandsons.

The rumor that Green died a millionaire is, like much of the folklore surrounding Aunt Jemima, not supported by historical evidence. This claim is unfounded, and all of the material we examined suggests that Green was not conspicuously wealthy. Therefore, we've rated this rumor false.

In February 2021, Quaker Oats announced that it was retiring the "Aunt Jemima" brand name and replacing it with the "Pearl Milling Company."