Albert Einstein has long skirted a definitive understanding of who he was beyond his scientific contributions, juxtaposed between a playful rendering of his character as a wild-haired, socially inept academic to an indispensable instrument of the Zionist project in the founding of the State of Israel.

After having fled Nazi Germany in 1932 – just one year before Hitler seized control of the country – Einstein eventually settled in Princeton, New Jersey, as a professor of theoretical physics. As one of the most well-known and respected figures of the global Jewish community, early Zionist leaders saw it as a necessary formality to offer him the presidency after the first president of Israel, Chaim Weizmann, died on Nov. 9, 1952.

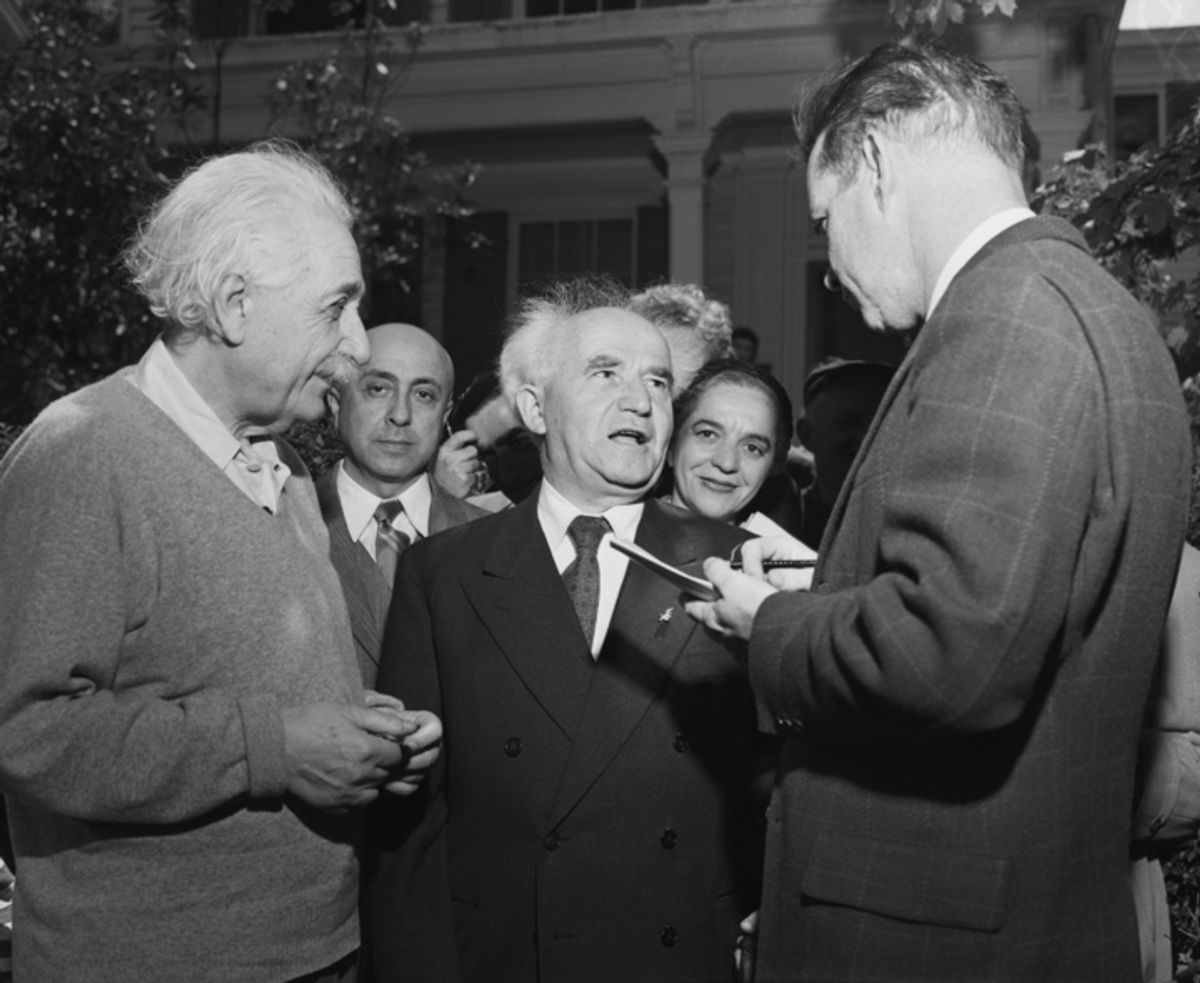

On Nov. 17, 1952, Einstein received a letter from Abba Eban, the Israeli ambassador to the United Nations offering him the presidency of Israel on behalf of the first prime minister of Israel, David Ben-Gurion. The beginning of the letter, according to the Jewish Virtual Library, read as follows:

Dear Professor Einstein:

The bearer of this letter is Mr. David Goitein of Jerusalem who is now serving as Minister at our Embassy in Washington. He is bringing you the question which Prime Minister Ben Gurion asked me to convey to you, namely, whether you would accept the Presidency of Israel if it were offered you by a vote of the Knesset. Acceptance would entail moving to Israel and taking its citizenship. The Prime Minister assures me that in such circumstances complete facility and freedom to pursue your great scientific work would be afforded by a government and people who are fully conscious of the supreme significance of your labors.

Einstein's response was brief. He said:

I am deeply moved by the offer from our State of Israel [to serve as President], and at once saddened and ashamed that I cannot accept it. All my life I have dealt with objective matters, hence I lack both the natural aptitude and the experience to deal properly with people and to exercise official functions. For these reasons alone I should be unsuited to fulfill the duties of that high office, even if advancing age was not making increasing inroads on my strength. I am the more distressed over these circumstances because my relationship to the Jewish people has become my strongest human bond, ever since I became fully aware of our precarious situation among the nations of the world.

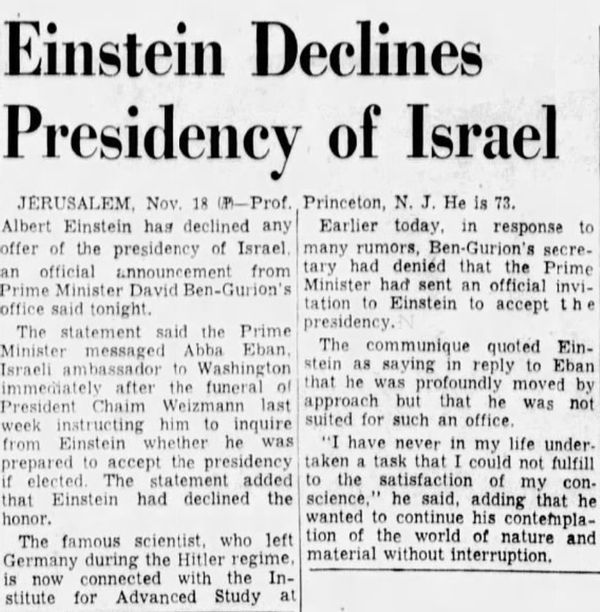

The news made its way to multiple headlines the next day, relaying an official statement from Ben-Gurion's office.

An article appearing in the Corpus Christi Caller-Times in Texas on Wednesday, Nov. 19, 1952. (Image via Newspapers.com.)

An article appearing in the Corpus Christi Caller-Times in Texas on Wednesday, Nov. 19, 1952. (Image via Newspapers.com.)

At the time, Einstein was 73 years old.

He told a guest who was staying with him at the time that the offer was "very awkward," and later relayed to the Jerusalem newspaper that had been campaigning for him that he did not want to "face the chance that he would have to go along with a government decision that 'might create a conflict with my conscience,'" as written in his 2007 biography by Walter Isaacson.

According to a TIME article published on Dec. 1 of the same year, "forgotten in the enthusiasm was the fact that Einstein, though sympathetic to Israel, had never been an ardent Zionist;" he believed in a "bi-nationalist" solution.

The term "Zionism" itself has evolved in its meaning since the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, originally defining a movement – founded by Theodor Herzl – arising out of the late 19th century to establish a new Jewish state in Palestine with the military and financial support of Great Britain.

Einstein also had worries "that the United Nations did not have the authority to prevent war," according to the American Museum of Natural History.

"Should we be unable to find a way to honest cooperation and honest pacts with the Arabs," he wrote to Weizmann (the former president of Israel) in a letter in 1929, "then we have learned absolutely nothing during our 2,000 years of suffering."

In 1946, two years before Israel was founded, Einstein testified to an international committee looking into Palestine saying, "the State idea is not in my heart." At the time, ardent Zionists were appalled that he would "break ranks." Once Israel had been established as a Jewish state, however, his attitude had someone changed.

"I have never considered the idea of a state a good one, for economic, political and military reasons," he wrote to a friend, according to Isaacson's biography. "But now, there is no going back and one has to fight it out."

Upon hearing that Einstein had turned down the offer of presidency, former Prime Minister Ben-Gurion was apparently "relieved," having told his assistant days earlier that "if [Einstein] accepts, we are in for trouble."

On Dec. 16, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi became the second president of Israel.