Every year, people in the U.S. practice the tradition known as daylight saving time, springing our clocks forward in April only to make them fall back in early November ("spring forward, fall back"). It can sometimes seem like a fool's errand — daylight saving time (DST) is an oft-targeted policy by politicians, and even in countries that observe it, it’s not very standardized.

In the U.S., it took until 2005 for the state of Indiana to opt into the practice, and that bill passed by just one vote. But two states (Arizona and Hawaii) and all territories in the U.S., two Canadian provinces, and half of Australia still don’t observe the practice. The tradition begs one question worldwide: Why in the world does the U.S. change its clocks? Even more — why doesn’t everyone do it?

While modern daylight savings has a history dating back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the concept is sometimes attributed to Benjamin Franklin. In a 1784 letter he wrote in the Journal de Paris, Franklin recommended that Parisians change their sleeping habits to match the hours of daylight and offered some quick back-of-the-napkin math to estimate how much money the French might save.

But nowhere in Franklin’s letter does he suggest changing the clocks. Even more, the letter is quite sarcastic. At one point, Franklin suggests that Parisians, “who with me have never seen any signs of sun-shine before noon,” simply did not believe him when he explained his “discovery” that the sun actually rose around 6 a.m. His solutions included firing cannons and ringing bells at dawn to rouse the Parisians from their slumber. Indeed, the conclusion scholars have drawn is that this letter is satirical in nature.

Instead, the first real proposal for daylight saving time was from New Zealand entomologist George Hudson in 1895. It was not particularly well received — one response to the proposal said, “Mr. Hudson’s original suggestions were wholly unscientific and impracticable. If he had really found many to support his views, they should unite and agitate for a reform.”

Hudson's plan called for New Zealand to shift the clocks two hours instead of one, but everything else about it looks relatively similar to what advocates for daylight saving time say today. Another early suggestion came from William Willet, a British industrialist, who suggested that the U.K. change its clocks by 20 minutes every Sunday for a month for a total of 80 minutes. In other words, contrary to popular belief, it's not farmers who have defended the practice. Cows and chickens do not particularly care whether the sun rises at 5:45 or 8:30, they just want to be fed because it's light out. Since farmers can't change their work schedules around livestock, they are actually some of the most vocal opponents of daylight saving.

For Hudson, an entomologist, he likely wanted more time to catch bugs while there was still light. In the 1907 pamphlet he published supporting the practice, meanwhile, Willet wrote that, "The brief period of daylight now at our disposal is frequently insufficient for most forms of outdoor recreation." He was an avid golfer.

In 1908, on the Canadian shore of Lake Superior, the clock-changing practice was officially adopted into law for the first time. A former school teacher and proponent of local athletics, John F. Hewitson, campaigned for the adoption of daylight savings in the twin cities of Fort William and Port Arthur, Ontario (they merged to form the city of Thunder Bay in 1970).

"He wanted to play baseball," Christina Wakefield, the city archivist for Thunder Bay, told Snopes via Zoom. "But he also gave other arguments, like that it would give parents added time to reconnect after their kids were in bed."

Hewitson's motivations aside, there was another, more economical reason for making a switch: The cities, which used Central Time, were a destination for freight trains coming from the Canadian prairies (also on Central Time) that would then ship their goods through the Great Lakes (those companies used Eastern Time). Workers in the two different time zones had different working hours, and scheduling problems ensued. So in 1908, the two cities adopted daylight saving time and coordinated a clock switch to Eastern Time on May 2, 1908, becoming the first place in the world to formally observe the practice.

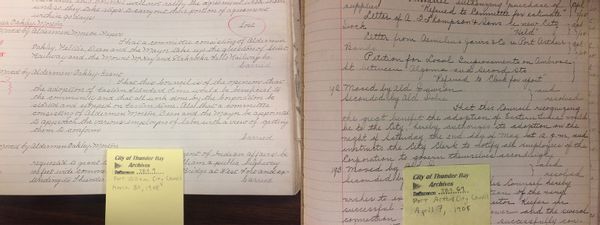

The minutes from the council meetings in which the two cities decided to adopt daylight saving for the first time. (City of Thunder Bay Archives, TBA 9 and TBA 69)

The minutes from the council meetings in which the two cities decided to adopt daylight saving for the first time. (City of Thunder Bay Archives, TBA 9 and TBA 69)

When it came time for the changing of the clocks the following year, both cities "sprung forward," but Port Arthur refused to move its clocks back to Central Time in November. In response, confused citizens wrote angry letters to local newspapers, and both city councils successfully petitioned the provincial government of Ontario to allow them to switch to Eastern Time without switching back, therefore adopting a permanent daylight saving time.

In 1916, the German and Austro-Hungarian governments instituted daylight saving time during World War I in an attempt to conserve materials for the war effort, and it stuck for a bit longer. Other countries followed suit, and in 1918, the United States passed the Standard Time Act, which mandated daylight saving time nationwide for the war effort. But the DST portion of the act was repealed the next year, again leaving the question up to local governments.

The practice formally returned in World War II when it was simply called “War Time," before falling back to the states and local governments in 1945. Finally, Congress standardized daylight saving by passing the Uniform Time Act of 1966, which forced each state to choose whether to change its clocks. Arizona and Hawaii, along with the aforementioned Indiana, opted out. While Indiana now follows DST, the other two states still do not.

Since 1966, the length of daylight saving time has been extended a few times, most recently in 2007, which placed the switches at 2 a.m. on the second Sunday in March and the first Sunday in November. In 1973, amidst an oil crisis, then-U.S. President Richard Nixon signed a bill into law that put the United States on permanent daylight saving time. It lasted for 15 months. Most recently, the U.S. Senate approved a bill that would again put the United States on permanent DST in 2022, but that bill failed in the House.

Regardless of whether you are a fan of the practice, there are two lessons to take away from daylight saving: The term is saving without the second ‘s,’ and telling time is a surprisingly complicated business.