Origin

Did Leonardo da Vinci — one of history's great geniuses, and a prolific inventor, artist, architect and 'Renaissance Man' — have such humility and perfectionism that he actually apologized on his death bed for the lack of "quality" in his life's work? Is it possible that the painter of the Mona Lisa and the Last Supper left this world feeling he had "offended God and mankind" with his deficiencies?

These are the surprising implications of a quotation widely attributed to Leonardo as his dying words. The quotation appears in social media memes, various compendiums of famous last words, and self-help guides. In November 2017 -- perhaps inspired by the world record-breaking sale of "Salvator Mundi," a painting of Christ attributed to Leonardo -- the quotation got a new audience on social media, when it was shared by the History Hustle Facebook page:

Despite being considered one of the most brilliant geniuses that has ever lived, Leonardo da Vinci's last words before dying were, "I have offended God and mankind because my work did not reach the quality it should have."

In an alternative version of the quotation, Leonardo is purported to have said "I have offended God and mankind by doing so little with my life." You can even buy a t-shirt featuring the words.

The original source of the quotation is a landmark text in art history: Giorgio Vasari's 1568 collection of biographies, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects (In Italian Le Vite de' Più Eccellenti Pittori, Scultori ed Architettori).

In it, Vasari gives an account of Leonardo spending his final moments in the company of King Francis I of France, one of his primary patrons. Notably, Vasari does not actually attribute the words to Leonardo as a direct quotation. Here's what he says, according to an 1879 edition of the book in the original Italian:

...Mostrava tuttavia quanto avea offeso Dio e gli uomini del mondo, non avendo operato nell'arte come si conveniva.

And here's the entire scene as translated into English by art historian Herbert Horne in 1903 (page 44:

At length, having become old, he remained ill many months, and finding himself near to death, he wished to be diligently informed of the matters of the Catholic faith, of the good way and holy Christian religion, and then with many sighs, confessed and was penitent; and although he was not able to raise himself well on his feet, supporting himself on the arms of his friends and servants, he wished to receive devoutly the most Holy Sacrament, out of his bed.

The King [Francis I], who often and lovingly was used to visit him, came to see him: whereupon he, out of reverence, having raised himself to sit upon the bed, giving an account of his illness, and the circumstances of it, showed withal how he had offended God and mankind in not having laboured at his art, as he ought to have done.

Whereupon he was seized with a paroxysm, the messenger of death, by reason of which the King having risen, and having taken his head, in order to aid him and show him favour, in the hope of alleviating his sufferings, his divine spirit, knowing that it could have no greater honour, expired in the arms of the King, in the 75th year of his age.

So instead of a direct quotation from Leonardo, we have a description of a conversation between Leonardo and Francis I by Giorgio Vasari, who was not present in the room.

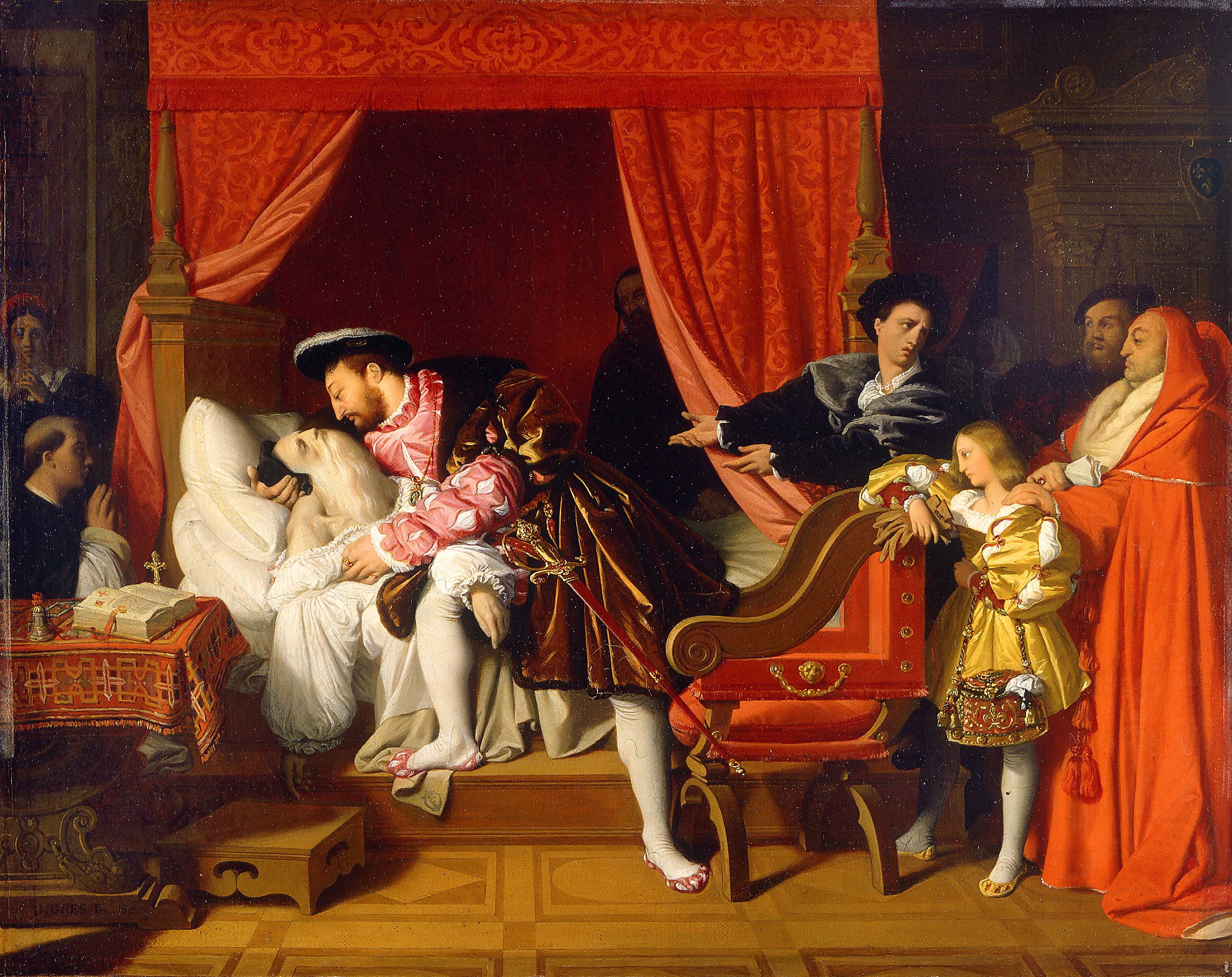

Vasari's dramatic account of the humanist Leonardo humbling himself before God before dying in the arms of a king inspired paintings by the French artists François-Guillaume Ménageot and Jean-August-Dominique Ingres (below).

However, its accuracy has been disputed by historians.

In his notes, Herbert Horne writes "The story that Leonardo expired in the arms of Francis I has long been called into question." In particular, Horne points to the fact that Leonardo died around Easter 1519 at Clos Lucé ("the chateau of Cloux") near the central French city of Amboise. At the time Francis I's court was in the royal palace at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, around 140 miles north.

Furthermore, Horne writes that Francesco Melzi -- a painter and pupil of Leonardo, who became a confidant and the executor of his will -- wrote to Leonardo's family to inform them of his death and bequests, but conspicuously said nothing about the purported presence of King Francis I at the time of his passing.

According to Gaetano Milanesi, the art historian who edited the 1879 Italian edition of Vasari's "Lives," Francis I's diary does not mention any visit to Clos Lucé at the time of Leonardo's death. Milanesi also notes that Vasari incorrectly stated da Vinci's age as 75 at the time of his death. In fact, he was 67 years old. This error does not enhance the credibility of Vasari's other claims.

A day before Leonardo's death on 2 May 1519, King Francis I issued a decree from Saint-Germain-en-Laye, according to Herbert Horne.

However, the science writer Michael White points to research by the 19th century historian Aimé Champollion, who stated that the decree was, in fact, signed by a chancellor in the absence of the King, leaving open the possibility that Francis I had visited Leonardo 140 miles away.

Whether or not Leonardo died in the king's arms, there is further reason to dispute Vasari's description of their conversation. In Leonardo: The First Scientist, Michael White points to Vasari's bias towards religiosity, which would undermine the objectivity of his account (page 260):

We should not take this account too seriously. Vasari, who was himself a deeply religious man, was fond of placing too much emphasis upon the religiosity of those about whom he wrote. Leonardo may have found some form of solace in conventional religion as he lay dying, but we have no proof of this.

In his 1888 translation of Leonardo's notebooks (page 1112), the German art historian Jean Paul Richter described Vasari's account of Leonardo's death in the arms of Francis I as an "incredible and demonstrably fictitious legend."

He added that the description of Leonardo regretting his lack of hard work was "evidence of the superficial character of the information which Vasari was in a position to give about Leonardo."

Ultimately, we don't know what Leonardo da Vinci's last words were. But we do know that the quotation commonly attributed to him is a modified version of the description of a conversation written 50 years after his death by an unreliable historian.