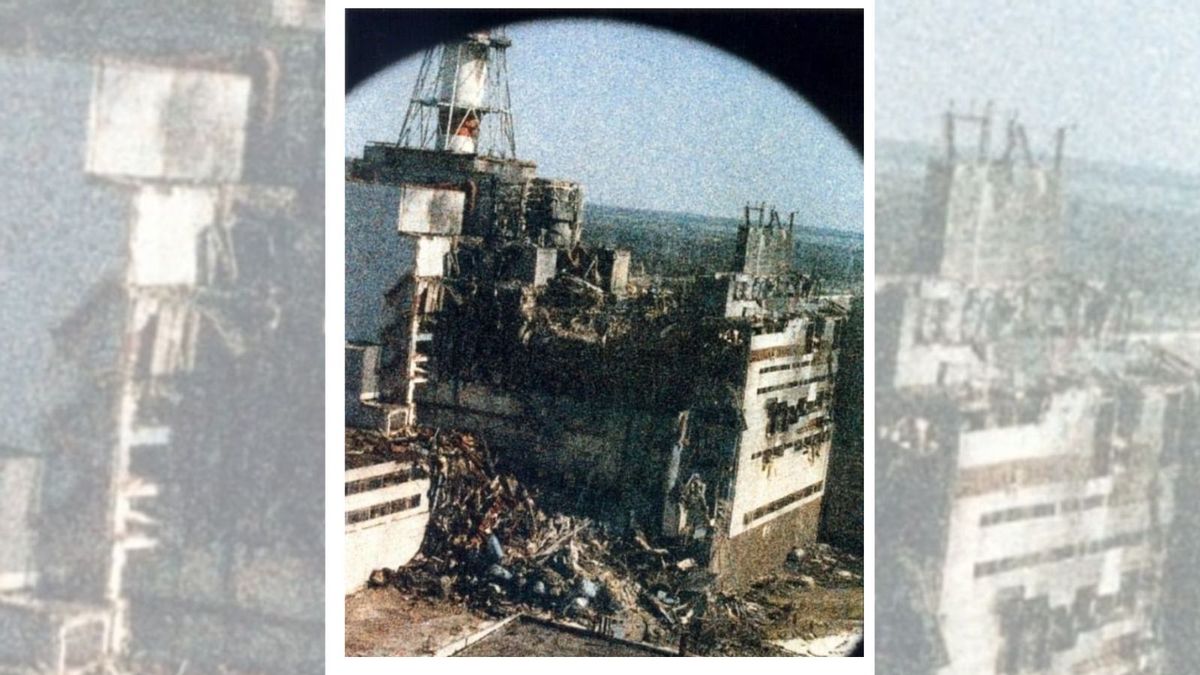

A viral photograph on Reddit claimed to show one of the first photographs taken at Chernobyl after the explosion of the nuclear reactor in Ukraine on April 26, 1986.

The post claimed it was shot 14 hours afterward.

The above photograph was indeed among the first taken just after the disaster occurred. Based on a number of accounts, it was also not the only shot of the site taken on April 26. Igor Kostin, as described by numerous news accounts, shot the picture in question, and by his own retelling was among the first photographers at the scene hours after the disaster.

A flawed nuclear reactor systems test at Chernobyl resulted in massive amounts of radioactive material being released into the environment. As we reported before, the incident, which occurred when Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union, had wide-ranging effects that lasted for decades in regions that included Belarus, the Russian Federation, and Ukraine. Effects included rising thyroid cancer cases among children and psycho-social impacts, including higher rates of depression, alcoholism and anxiety.

The Guardian shared Kostin's photograph in an online series of images taken in the disaster's aftermath. The story stated photographers arrived on April 27, 1986, and credited Kostin with the image in question:

The first photo to be taken of the reactor, at 4pm, 14 hours after the explosion. This was taken from the first helicopter to fly over the disaster zone to evaluate radiation levels. The view is foggy due to radiation, which also explains why the shot was not taken too close to the window. Later, radiation experts learnt that at 200 metres above the reactor, levels reached 1500 rems [referring to a unit of radiation dosage], despite the fact that their counters did not exceed 500 rems.

The Guardian date, however, contradicts the dates published in The Associated Press and in Kostin’s own book, which noted that photographers arrived on April 26. The first explosion took place at 1:23 a.m. on April 26. Kostin described getting woken up with a call about the incident on April 26, and leaving his house to take a 45-minute helicopter ride to the site just as the sun was rising.

An Associated Press caption for a different photograph of the reactor taken from an aerial angle by Volodymyr Repik — one of the three photographers at the scene in the helicopter in the immediate aftermath — was also reportedly taken on April 26, 1986, the same day as the explosion. We do not know if this was shot before or after Kostin’s photograph:

Only three Tass [Russian news agency] photographers were allowed in -- Volodymyr Repik, Igor Kostin and Valery Zufarov. Two later died of radiation-related illnesses and Kostin suffered from the effects for decades before dying in a car accident in 2015. The Chernobyl nuclear power plant explosion was only about 60 miles from photographer Efrem Lukatsky's home, but he didn’t learn about it until the next morning from a neighbor. Only a few photographers were allowed to cover the destroyed reactor and desperate cleanup efforts, and all of them paid for it with their health.

Kostin detailed the experience in his book “Chernobyl: Confessions of a Reporter.” He wrote that he was a photographer for Novosti agency not Tass (though they were both state-owned). All of his photographs from that day were damaged with the exception of the above image:

I opened the window, mechanically, as I always do, in order to avoid reflections. I got my camera ready and took a photograph. A big puff of hot air filled the cabin of the helicopter. At once, I wanted to scrape the bottom of my throat. It was a new and strange feeling. I swallowed my saliva with difficulty. Probably the toxic smoke of the fire. I stopped myself from coughing and pointed my lens towards the ground. I made my first shots, about twenty of them. Suddenly, my camera locked. I forced the release button, but nothing. The mechanism had the flu. I was furious. I jammed it fiercely for a few seconds, in vain. The pilot flew one more time over the plant. Unable to take more photos, we flew back without even touching down. All that trouble for only twenty photographs! In Kiev, while developing it, the film was covered with an opaque surface. Almost all the photographs are entirely black, as if the camera had been opened in full light and the film exposed. I did not understand it then, but it was due to the radioactivity. Marie Curie had been confronted by the same experience when she isolated radium. The radiation makes an impression on the film or the photographic plates. Only the first photographs seemed less damaged. Undoubtedly they had been protected by the roll casing. Struggling with the film, I ended up obtaining an acceptable photograph that I sent to Moscow, to the Novosti agency main office. It was not published. But by then I already knew that I was going to return to Chernobyl to take photographs.

The photograph in question can be found on page 6 of the book, which is available on The Internet Archive. The caption stated: “This is the only photo in the world taken the same day as the accident.”

Yet another photographer was present that day, according to other reports. A 2006 BBC story shared an account by Anatoly Rasskazov, who was a staff photographer at the plant and who was reportedly allowed in on the day of the explosion. Rasskazov described how he shot photographs from the air and on the ground:

There were rumours of a minor accident at the station, but I cleaned the windows of our flat in Pripyat as usual. Then at about 9am I was summoned urgently to the station.

No-one believed that something so awful could occur.

I went down into the bunker where the authorities were working, and I understood that they did not really know whether the active zone of the reactor was destroyed or not. They wanted pictures taken from above to see what had really happened.

In the helicopter, there were two soldiers and two civilians from Atomenergo, who had flown down from Moscow. There was so much ash flying around, it was impossible to take photographs through the glass. I said, "Comrades, we have to open the window." They protested, saying it would contaminate the helicopter. They knew what it was, the material rising up from the reactor.

But the window was opened. I leaned out with my camera, a wide-format Kiev-6, and a soldier held my legs to stop me falling. Then I doubled up with a Zenit.

He went on to describe how he took a number of pictures from the ground by driving around in a fire engine and drove up close to the ruins of one of the reactors. However, when he tried to develop his photographs, he faced a similar challenge to Kostin's:

I develop the first film, from the Zenit, and it is black, completely burnt out by radiation - probably from the graphite block. I think, "That's it. It's all over." But the second film, from the other camera was successful, only slightly clouded. When I got to the station the First Department [security] took the prints, numbered them and took the films. "Everything you saw and heard - keep your mouth locked!" they said. From the photographs it was clear that the active zone was badly damaged. Until May, no-one else was allowed to take pictures.

Rasskazov suffered serious health complications in the decades after his time photographing the ruins at Chernobyl. His photographs were eventually published in a book, but he said that he was never credited with them. The photographs can be seen in the BBC article here. Per the Chernobyl Museum website (via Google Translate), we learned he photographed the destroyed power unit around 3 p.m. on April 26.

Anna Korolevska, who was a deputy director for the Chernobyl Museum in Kyiv, Ukraine, told NBC News in 2011 that Rasskazov made a video of the destroyed reactor and submitted it to a special commission working in a bunker close to the plant, and that the Soviet secret police seized his photographs submitted later. Only two of his photographs were published in 1987, without crediting him, according to NBC News.

We reached out to the Chernobyl Museum in Kyiv for more information about Kostin and Rasskazov. We will update this post accordingly.

In short, while Kostin took one of the first photographs of the Chernobyl disaster, other professionals also shot photographs on the day of the incident.