In early 2022, Snopes readers inquired about an April 2021 article from Yahoo News that described the U.S. Postal Inspection Service function known as the Internet Covert Operations Program (iCOP). The headline read: "The Postal Service is running 'covert operations program' that monitors Americans' social media posts." For example, it mentioned a case involving an alleged Proud Boy. We previously described the Proud Boys as a "volunteer 'security' force that had openly advocated violence and white supremacy."

In our research, we also found that Politico reported about iCOP and the USPIS doing some "internet sleuthing" after the Jan. 6, 2021, riot at the U.S. Capitol, as well as other news that said they were "hacking into hundreds of seized mobile devices."

Here's what we know.

Official Statement

First, we confirmed with the USPIS the authenticity of a statement about iCOP. They described the program as follows:

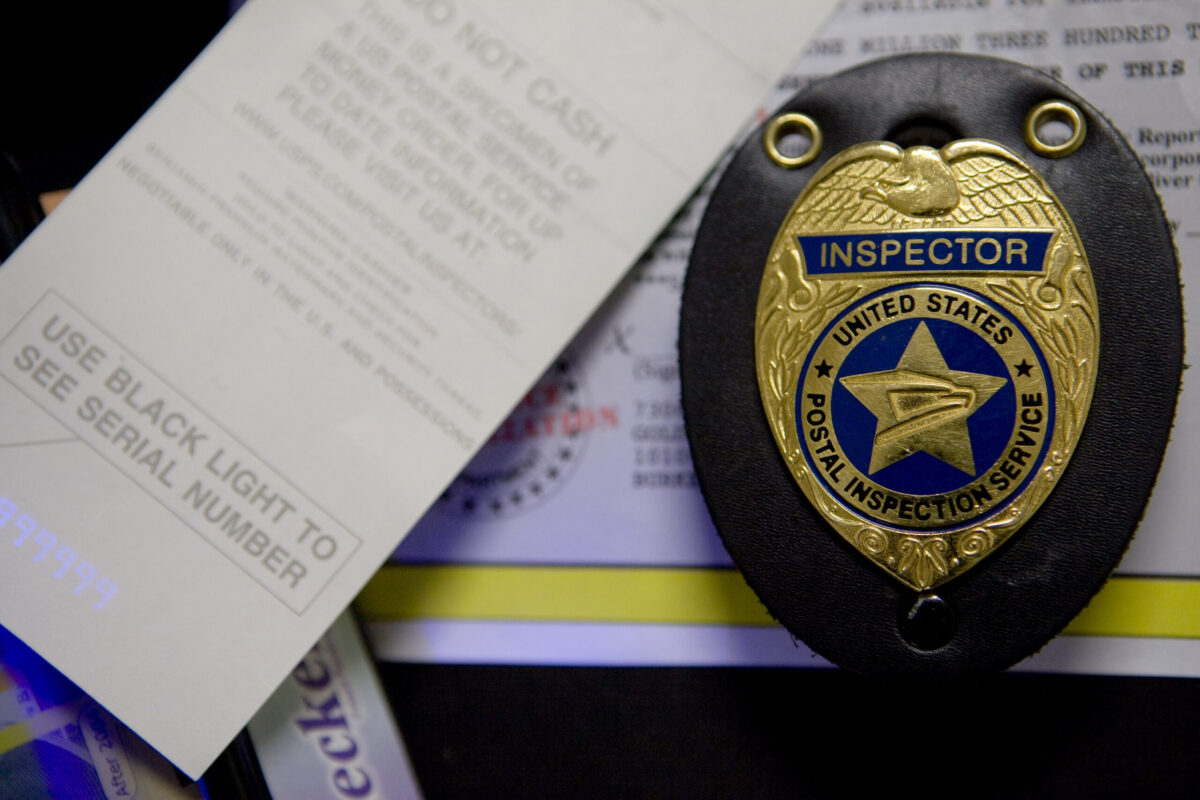

The U.S. Postal Inspection Service is the primary law enforcement, crime prevention, and security arm of the U.S. Postal Service. As such, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service has federal law enforcement officers, Postal Inspectors, who enforce approximately 200 federal laws to achieve the agency’s mission: protect the U.S. Postal Service and its employees, infrastructure, and customers; enforce the laws that defend the nation's mail system from illegal or dangerous use; and ensure public trust in the mail.

The Internet Covert Operations Program is a function within the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, which assesses threats to Postal Service employees and its infrastructure by monitoring publicly available open source information.

Additionally, the Inspection Service collaborates with federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies to proactively identify and assess potential threats to the Postal Service, its employees and customers, and its overall mail processing and transportation network. In order to preserve operational effectiveness, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service does not discuss its protocols, investigative methods, or tools.

While iCOP may be new, the USPIS has been around since the 18th century, as The Washington Post reported. Some readers may remember that it was the USPIS and not another government agency that arrested Steve Bannon, a former adviser to then-U.S. President Donald Trump, on fraud charges.

'Assesses Threats'

We were unable to obtain additional details from the USPIS about iCOP. Based on our own experiences monitoring social media accounts for past investigations, the statement raised further questions in our minds.

Specifically, the statement said that iCOP "assesses threats to Postal Service employees and its infrastructure by monitoring publicly available open source information." The keywords there appeared to be "publicly available open source information."

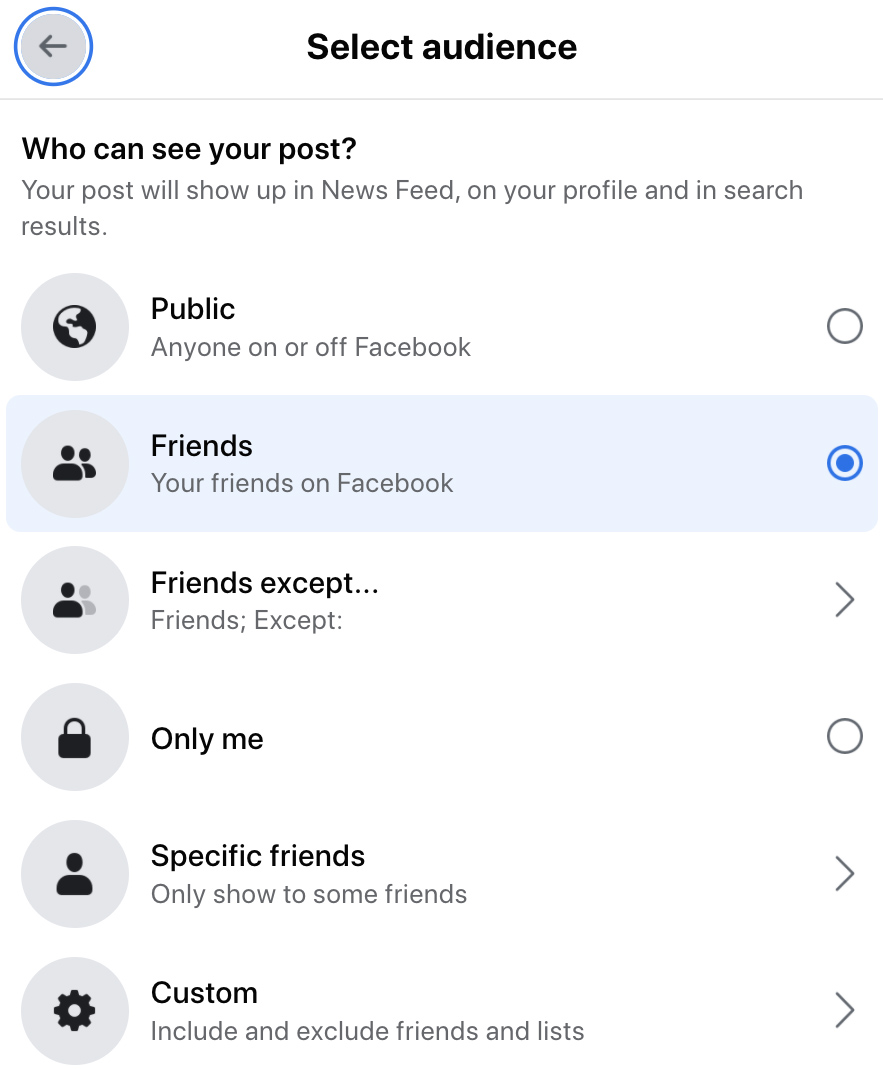

Using Facebook as an example, what would "publicly available open source information" constitute? Posts with a privacy option set to "Public" are publicly available. However, what about a post that was set to be viewed by "Friends" only? Facebook might define that as private, but what about the USPIS?

Would a member of the public being accepted into a private Facebook group also fall under the language of "publicly available open source information," since it could theoretically be viewed by members of the public? It might not be "Public" by Facebook's definition, but the USPIS's definition might be different. We simply don't know. They would not provide further comment.

Jan. 6, 2021

On Sept. 27, 2021, Politico reported about what iCOP and the USPIS did following the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol. In summary, the article said that iCOP was investigating various online postings made around the riot:

On Jan. 11, the United States Postal Inspection Service’s Internet Covert Operations Program — better known as iCOP — sent bulletins to law enforcement agencies around the country on how to view social media posts that had been deleted. It also described its scrutiny of posts on the fringe social media network Wimkin.

Few Americans are aware that the same organization that delivers their mail also runs a robust surveillance operation rooted in an agency that dates back to the 18th century. And iCOP’s involvement raises questions about how broad the mandate of the Postal Service’s policing arm has grown from its stated mission of keeping mail deliverers safe.

The documents also point to potential gaps in the Jan. 6 select committee’s investigation by revealing concerns about a company it is not known to be scrutinizing. And those documents point to a new challenge for law enforcement in the post-Jan. 6 era: how to track extremist organizing across a host of low-profile platforms.

We were unable to obtain further details from the USPIS about this subject. It's unclear what it meant regarding "how to view social media posts that had been deleted." One way to do this is to look to sources such as Google's caching or other archive methods that mirror websites for the purposes of archiving them.

According to the U.S. Capitol Police and the Metropolitan Police Department in Washington, D.C., 140 law enforcement officers were injured at the Capitol on Jan. 6. One officer died the next day and others have since taken their own lives. Some of the participants who entered the building carried "Blue Lives Matter" and "Thin Blue Line" flags.

Seized Mobile Devices

Also in our research, we looked at February 2022 reporting from Just The News that had the headline, "Postal Service hacking into hundreds of seized mobile devices, tracking users' social media posts."

It cited a real report from the USPIS website that was published in fiscal year 2020. In the official report, it confirmed that they did obtain technology that allowed them to break into seized mobile phones, and that it had been used hundreds of times, just as the headline said:

FLS (Forensic Laboratory Services) remains focused on technological advancement, as demonstrated by the procurement and/or development of new equipment, hardware, and software to support Inspection Service investigations. The Cellebrite Premium and GrayKey tools acquired in FY 2019 and 2018 allow the Digital Evidence Unit to extract previously unattainable information from seized mobile devices. During FY 2020, 331 devices were processed, and 242 were unlocked and/or extracted by these services. The success of the program and ever-increasing demand for services required the purchase this year of a second GrayKey device for use on the East Coast.

We reached out to the USPIS for comment about the tools that allow extraction of data from seized mobile devices. They told us: "Only a limited number of individuals have access to these tools and they are used in accordance with legal requirements. A search warrant, court order, or other constitutionally permissible situation must exist prior to any digital evidence examination of cell phones."

The reporting from Just The News also described lawsuits that have attempted to stop the program and obtain more records about what it does via Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests.

In sum, not much is known about iCOP, but based on publicly available information, the USPIS program appeared to be used to assess threats and obtain information regarding past cases of extremism or the documented plans of potential future extremist activity.