As we've had occasion to point out previously, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson had a complicated relationship with issues of race. Born and raised in the South in the early part of the 20th century, Johnson grew up immersed in the prejudices of that time and place, then carried them with him into his nascent political career. MSNBC reporter Adam Serwer wrote:

For two decades in Congress he was a reliable member of the Southern bloc, helping to stonewall civil rights legislation. As [biographer Robert] Caro recalls, Johnson spent the late 1940s railing against the "hordes of barbaric yellow dwarves" in East Asia. Buying into the stereotype that blacks were afraid of snakes (who isn't afraid of snakes?) he'd drive to gas stations with one in his trunk and try to trick black attendants into opening it. Once, Caro writes, the stunt nearly ended with him being beaten with a tire iron.

Yet by the time Johnson became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, he was ready to plow all of his political capital to the passage of the civil rights legislation initiated by his predecessor. By most accounts, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 couldn't have become law when it did had not LBJ personally wheedled, cajoled, and shamed his former colleagues in the House and Senate into voting for it. One of the secrets of his success was the ability to speak the racially insensitive language of his fellow Southerners. He understood them. He understood their reluctance and in some cases downright refusal to tear down the walls of racial segregation. He knew racism from the inside, and he knew well the role the rich and powerful played in promulgating it.

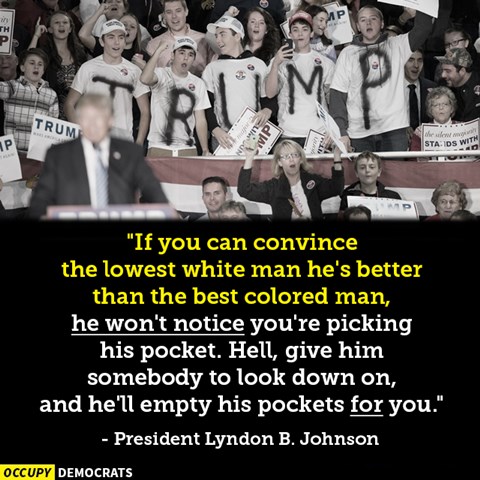

That's the context of one of the most famous statements on race ever attributed to President Johnson, an off-the-cuff observation he made to a young staffer, Bill Moyers, after encountering a display of blatant racism during a political visit to the South. Moyers tells it in the first person:

We were in Tennessee. During the motorcade, he spotted some ugly racial epithets scrawled on signs. Late that night in the hotel, when the local dignitaries had finished the last bottles of bourbon and branch water and departed, he started talking about those signs. "I'll tell you what's at the bottom of it," he said. "If you can convince the lowest white man he's better than the best colored man, he won't notice you're picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he'll empty his pockets for you."

In the blunt vernacular that he loved to use, LBJ was describing what the television pundits of today would probably call the politics of resentment and divisiveness. It is still very much with us.