A popular (but completely citation-free) science meme suggests that a pregnant mother's fetus can send its own stem cells to its mother to repair damaged organs. Although any memes of this nature run the gamut from "nodding acquaintance with truth" to "has never met truth and never will," this particular one is mostly accurate.

While the wording of the meme is problematic for two reasons (first, the meme's text generally says 'baby', which is incorrect as that term implies a birth; second the wording implies a conscious decision on the part of the fetus to send its tissues as a heroic gesture), the science behind the claim is actually fairly solid.

The transfer and incorporation of fetal stem cells into a mother's organs is referred to as fetomaternal microchimerism. A 2016 paper in the Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology defines the phenomenon thusly:

Fetal cell microchimerism is defined as the persistence of fetal cells in the mother for decades after pregnancy without any apparent rejection. Fetal microchimeric cells (fmcs) engraft the maternal bone marrow and are able to migrate through the circulation and to reach tissues.

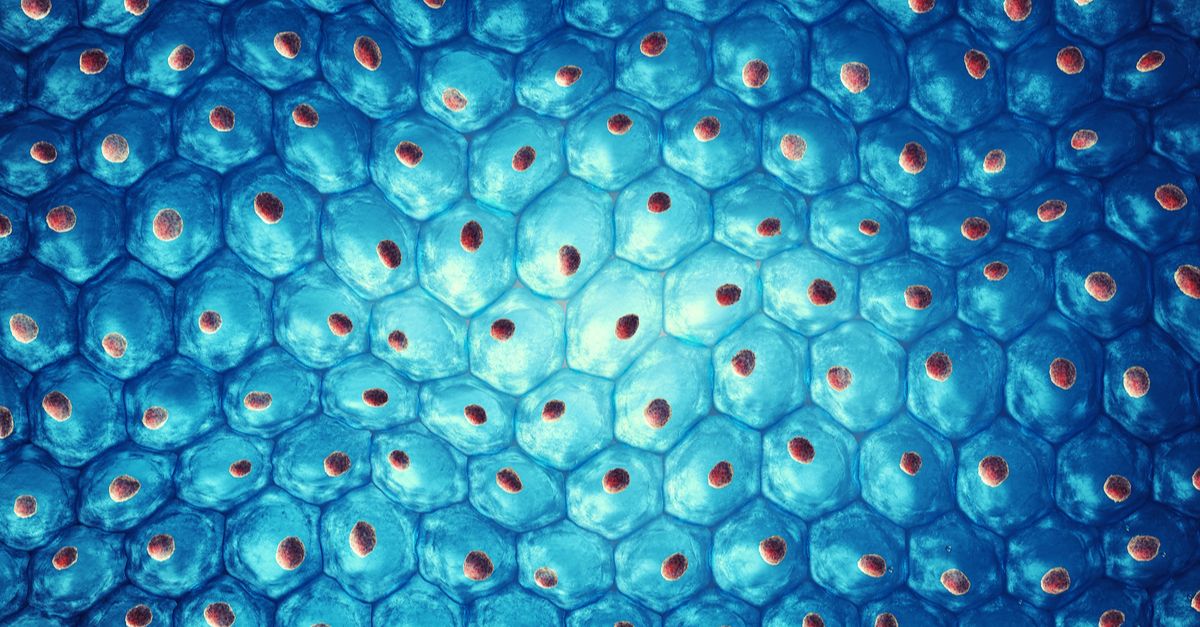

Stem cells are essentially blank slates that have ability to turn into a variety of different tissues and, as such, play a big role in the development of a fetus. The idea with fetomaternal chimerism is that those cells can be transported out of the fetal system and become fully integrated into the mother's system despite the cells' distinctly different genetics.

Scientists have been aware of fetomaternal microchimerism's existence (in broad terms) for decades. A 1996 study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, for example, found that in humans, genetically distinct cells from a male fetus persisted in the mother's body as long as 27 years after birth.

Later research has demonstrated that these fetal cells can be found in multiple organs in both human and laboratory mice mothers:

Fetomaternal transfer probably occurs in all pregnancies and in humans the fetal cells can persist for decades. Microchimeric fetal cells are found in various maternal tissues and organs including blood, bone marrow, skin and liver.

A 2015 study published in the journal Circulation Research addressed the issue of fetal stem cells actually healing maternal organs. In this study, researchers mated female mice with transgenic male mice that were tagged with a fluorescent protein that allowed the researchers to trace the flow of the fetus's stem cells from the mother's placenta into its heart while they induced cardiac injury to the mother. They found that fetal stem cells directly targeted the damaged cardiac cells and fully integrated themselves into the mother's heart. This research, the authors state:

Points to the presence of precise signals sensed by cells of fetal origin that enable them to target diseased myocardium specifically and to differentiate into diverse cardiac lineages. Most notable is their differentiation into functional cardiomyocytes that are able to beat in syncytium with neighboring cardiomyocytes, thus potentially uncovering an evolutionary mechanism whereby the fetus assists in protecting the mother's heart during and after pregnancy.

While this study was performed on mice, there is a wide body of research that suggests similar phenomena could occur in humans. There is still much research to be done, however, on the overall mechanisms behind this process and the totality of effects it may have on both fetus and mother.