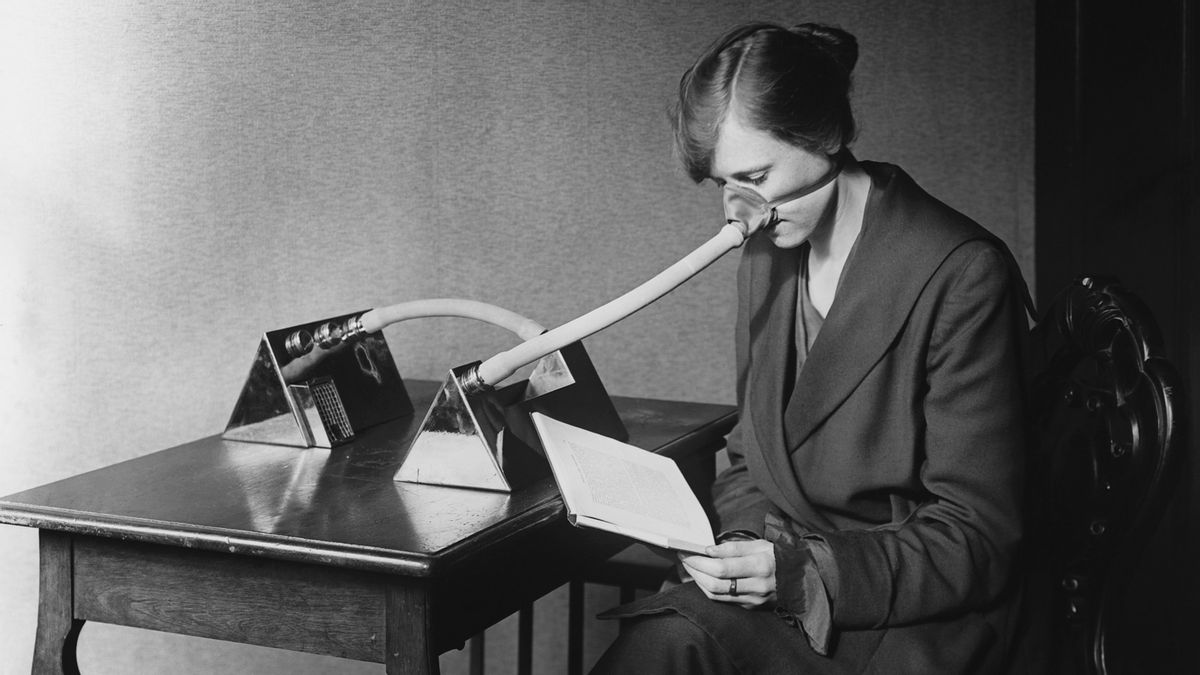

Since early 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic raged both across the U.S. and the world, various photographs of masks worn during the 1918-1920 influenza pandemic were shared online, as we noted with other stories in the past. One such picture that was often posted on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram showed a woman sitting at a desk with a unique-looking mask over her nose. The social media posts claimed that the photograph showed a mask being worn in February 1919.

In the picture, a hose could be seen going from the woman's nose to a mechanical device on the desk, which then extended to a second device with another hose. This was a real photograph that had been properly captioned by social media users.

The COVID-19 vaccine makers at Pfizer once published a story that featured the black-and-white picture of the woman. The article referred to the device on the woman's face as a "mechanical nozzle mask." It also described what the world was like during the Spanish flu pandemic:

People were asked to wear masks, usually made out of fabric, in public as a first line of defense against contracting and transmitting the disease, and were denied admittance to streetcars, offices, and other public places if mask-less. Above, a woman dons a mechanical nozzle mask in February of 1919.

People tried all sorts of secondary defenses in the event their masks failed. Pamphlets suggested chewing food carefully and avoiding tight clothes and shoes, and there was a surge of support for legislation that would ban public coughing and sneezing. Home remedies included gargling a mixture of sodium bicarbonate and boric acid, stuffing salt up noses, and eating onions with every meal.

In the 1930s, the source of influenza was discovered to be viruses, not bacteria. By the end of the decade, in 1938, Jonas Salk and Thomas Francis developed the first vaccine against flu viruses. Today, about half of Americans get an annual flu shot.

On Dec. 1, 2018, just a little over one year before the first COVID-19 case was recorded in the U.S., The Associated Press published an article about the origins and impact of what was then called the Spanish flu pandemic.

"It's estimated the virus contributed to the deaths of between 50 million and 100 million worldwide, representing between 3 percent and 5 percent of the world's population," the reporting said.

The story also mentioned that the pandemic was believed to have originated not in Spain, as the name "Spanish flu" implied, but rather in Kansas:

In the United States, the [Spanish] flu may have struck as many as 30 percent of the nation's population, killing more than 500,000 people. It is the second deadliest event in American history, behind only the Civil War, and alone dropped the nation's life expectancy by 12 years.

"Spanish" flu is a misnomer, and the strain is theorized to have actually developed in Kansas. Because newspapers on both sides of World War I censored most early news of the outbreak for the sake of public morale, Spain, which remained neutral, freely reported on influenza, giving the impression it had originated there.

America's troop mobilization in World War I spread the disease across the country and eventually into Europe once deployed. Stateside military encampments, with their crowded and often unsanitary quarters, became hotbeds of disease.

The first cases were thought to have developed among soldiers at Fort Riley, Kansas, around March 1918. Camp Sherman in Chillicothe, Ohio, suffered an astonishing 1,777 deaths due to influenza that year - the bodies of soldiers grimly "stacked like cordwood" outside the morgue. In Maryland, Camp Meade reported 77 deaths in just one 24-hour period, including 19 soldiers from West Virginia.

We weren't able to locate a name for the woman in the photograph, nor could we find credible records that listed an exact day of when it was captured. However, the picture was indeed real, as evidenced by this page on the Getty Images image-licensing website.